Rich Family’s Secret Nanny Scandal — What a Nurse Found Will Shock You

A rich man’s son screamed for weeks… But the nurse from a tough neighborhood found metal in his scalp that no scan could see.

“Alejandro, call another neurologist,” Lucía said. She spoke like she was reciting a brand name, like she could order pain away. “He’s fine. He’s dramatic.”

“He’s not dramatic,” Alejandro replied. “He’s seven and he keeps screaming at night. You hear him. I hear him. You hear it now—don’t you?”

From the study the crying threaded up through the marble and glass like a live wire. Tomás had been crying for three weeks. Alejandro had taken him to clinics, to specialists in Mexico City and Monterrey, to an acupuncturist his brother swore by. They’d bandaged his hands for imagined seizures, run the cameras, administered sedatives. Nothing stopped the crying.

Don Rafael knocked and came in with the new nurse’s file. “She waits downstairs, sir. The agency says she’s thorough. From La Guerrero.”

Lucía’s nose wrinkled. “La—what?”

“She’s from a tougher neighborhood,” Alejandro said. “That doesn’t mean anything. Let her try.”

The nurse who entered smelled of laundry soap and rain. Her jeans were worn; her braid was tidy. She set a small bag on the table and did not look at Lucía’s dress.

“Marisol Vega,” she said. “Pediatric nurse. I worked in a home clinic and in emergencies. You can tell me what you think is best.”

Lucía folded her arms, a fence around her posture. “We’ve had fourteen doctors. If you can’t read an MRI, we don’t need—”

“I read the child,” Marisol interrupted. Her voice was calm, useless against wealth and habit. “May I see him?”

Upstairs the crying pushed like a tide. Tomás lay on the playroom floor, curled, clutching his head. Lucía hovered near the doorway, a cocktail in hand like a false flag. Alejandro watched Marisol kneel by the boy.

Marisol’s hands did what hands do when they have practiced on bruises and fevers and broken bones. “Can you tell me where it hurts?” she asked, Spanish shaping each syllable like a light.

Tomás’s little eyes were two dark coins. “Here,” he said, touching the crown of his head.

Marisol felt the scalp. Then she asked, “Strong light? Magnifier?”

Lucía scoffed. “You can’t bring a lamp into his head.”

Marisol produced a simple penlight and a small magnifying glass from her bag. She held them like tools she’d known since she was a girl. Under the lamp she saw tiny scars. Tiny dark points.

“What is that?” Alejandro demanded.

“Metal,”

Lucía’s laughter was brittle. “You mean something was embedded—how—”

“Someone wanted him to hurt,” Marisol said. “They wanted a pain that didn’t leave marks on an MRI, a pain that can be disregarded as nerves or behavior.”

“Who would do that?” Alejandro whispered. The world had always been a currency he could negotiate. Pain wasn’t a ledger.

Marisol worked silently. She extracted one piece, then another. Tomás hurt when she moved her fingers; he sucked air through his teeth and then, slowly, the screaming button seemed to click off. He breathed.

When Marisol finished there were eighteen small, irregular pieces in the palm of her hand. Wire. tacks. Little things shaped like promises gone sour.

“He says it’s better,” she told Alejandro. The two men looked at each other like sailors who had seen a storm break a hull.

Lucía stepped back. “This is impossible. Who would—”

“Who cared for him?” Marisol asked.

“The nannies,” Lucía said, automatically. “Clara left a month ago.”

Clara. The name came with a pause like a bad silence between chords. Alejandro had been young when Clara had been hired. She was seventeen then, a girl with a shy smile who had folded clothes like secrets.

“She left,” Lucía said. “She was… difficult. She ran off. Took a bus.”

Marisol had to sleep that night on the couch in the servant’s wing. She didn’t ask for permission. Her bag was small and smelled of antibiotics and lemon. Outside the window, Lomas de Chapultepec glittered with apartments and restaurants and invisible bills. Inside, when Tomás finally slept, Alejandro sat up with him and watched his chest rise and fall as if it were a market price that could change.

Three days later Marisol found a loose floorboard in the service corridor. She never believed in coincidences. Under the board was a small diary, edges frayed, lines written in a tight, breathless hand.

The last entry was short.

“Tomás is my son. Lucía hurts me. She took him to pay me back for being seventeen. Tomorrow I tell Alejandro.”

Marisol’s stomach folded like a letter. She read the lines twice, then a third time. She put the diary in her bag and walked into the afternoon like a person carrying a secret cold enough to break glass.

She asked quiet questions. She met faces that looked away. The staff shifted like fish in a crowded bowl. Don Rafael had been there a long time. “Clara—she was sweet,” he said. “Just a young thing. Alejandro—” He stopped. He had witnessed a lot.

Lucía’s smile narrowed. Alejandro confronted her in the kitchen, where the light made her skin a false paper. “Did you take a baby?” he asked. He felt absurd asking a question that could break everything.

Lucía’s eyes became a machine. “Alejandro, of course not. Don’t be dramatic.”

“This diary—”

“It’s nonsense,” she said. Her voice had the flatness of a rehearsed alibi. She set a glass down too hard. It tinked like a verdict.

Marisol kept looking. She returned to the garden where the roses were obsessively arranged in beds like small economies of color. She knelt in the soil with her hands in gloves. She dug where the soil was soft and where the gardener’s paths met. There was a hollow, a small place that had been softened and then smoothed again.

At dusk her shovel hit something that was not stone. It sounded dull and final, like closing a lid.

She brushed clay away and found hair, knotted, and a palm that had been folded beyond breath. It was Clara.

Marisol ran to Alejandro’s study. The phone rang in her hand but she didn’t answer the politeness of police or lawyers. She said the word “body” and Alejandro’s face folded in a way that was both animal and very human.

Lucía was waiting on the staircase, a small gun in her hand like the final prop in a play. Her face had that thin look of someone who had told herself stories for a long time.

“It was supposed to be simple,” she said. “I told her she couldn’t be with him. I told her she had to leave. She came back. She kept showing up. I couldn’t let her ruin—us.”

“Why torture him?” Marisol asked. “Why the fragments?”

Lucía’s voice lost its practiced edge. “I wanted to punish. I wanted to make him throw it out in screams so that he would learn not to love what he shouldn’t. It was—” She stopped and laughed a small, dry laugh. “It was a way to mark her.”

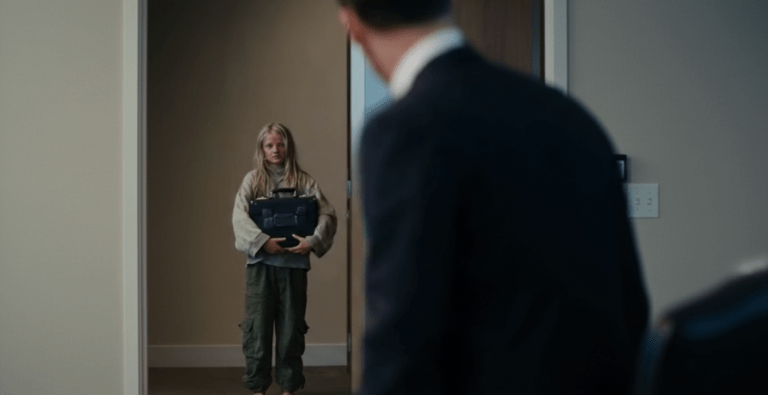

Tomás stood in the doorway then. He looked small and oddly luminous, as if the house had been built to cast him in a certain kind of light. He had been listening. “Mom?” he said. The word fell like an accusation and a question.

Lucía’s hand shook. The gun clattered. She collapsed into confession like a tired animal. She told them about the pregnancy she had faked, the hospital records she had altered, the payments she had made to erase Clara. She told them about the fury that had lit her up and the disease in her mind that had told her to bury the past.

The police were a blur of uniforms and clipboard pens. They took statements. They moved like people doing their work on stage.

Inspector Elena Vega stood at the periphery of the flurry, dry-lined face like a bookmark. She had the badge of experience and the ache only a mother can understand. Elena had always kept her life split into neat parts: she was a cop, and she was someone who had loved her daughter and had buried her own anger in the work. When she looked at Marisol there was a private curve in her face.

“You did good, niña,” she said. “You kept going.”

Clara’s story unspooled like thread. She had been young and pregnant and terrified. She had loved Alejandro in a way that was both simple and complete. Lucía had been clever and cruel, and the house had a way of keeping secrets that made them older than they were. Clara had stayed nearby as a shadow. When she had started to talk about telling Alejandro, Lucía had become sharp and then lethal.

The trial took the months it takes for justice to separate itself from the rush of headlines. Lucía clung to a defense of fear and one of control. The jury found it hard to reconcile a woman of status with the day-by-day cruelty the evidence suggested. The judge read things into the record that smelled like pity and like finality.

Tomás learned the truth in pieces. Alejandro wanted a clean telling, a script that would make a neat family picture. Marisol disagreed. “Tell him small truths,” she said. “Tell him the heart of it. Let him ask.”

So they sat on the terrace under a jacaranda that had been planted after the roses had been dug up. Its branches threw purple confetti like forgiveness. Tomás’s questions came slow. He wanted to know why his head had hurt and who had put the pieces and why someone would hide a mother like that.

Lucía’s name was a sound that opened new rooms in the boy. He learned, painfully, that Clara had loved him enough to try to return and that she had paid with her life. He learned that his father had made mistakes that were human and heavy. He learned that Marisol had smelled out a wrong and had refused to let it sit.

“Was it my fault?” he asked once, small and terrible.

“No,” Alejandro said, voice stripped. “Never. You were a child. You were safe in how you were. We failed you around you. But you are not the mistake.”

Marisol sat back and let the two of them speak. She had not come for thanks. She had come, first, because an ache in a child was also an ache in a city, and second, because the world in her neighborhood had taught her to keep looking.

Months passed. The house changed. Lucía’s portrait came down. The staff rebalanced; some left, some stayed. Alejandro found a steadier habit of listening. He took nothing for granted that sound could break.

Tomás stopped waking at night. He played soccer on a lawn not native to the neighborhood but familiar along a curve of grass. He learned to paint, to climb, to name feelings. He learned, slowly, to sleep without the phantom pressure on his scalp.

Marisol returned to La Guerrero when her contract ended. She visited on holidays, sometimes bringing a pie, once with a thermos of coffee. Elena would meet her at intersections and exchange news like old confidants. But Marisol stayed part of the household as a presence more than as a paid hand. Alejandro paid her well without showing off the amount. He had learned things about worth that were not bills.

On Tomás’s eighth birthday they planted a new tree where the roses had been. The jacaranda now cast a canopy of purple over the place where the dirt had once been cleaned for a grave. The family gathered in a quiet that felt earned. Alejandro read a book aloud in halting English that the nanny—Clara—had once used to teach colors. Marisol watched the boy who once screamed for weeks and felt nothing dramatic inside, only a solid gladness that had edges and that would hold.

The past was still there, a dark ledger in a drawer. Lucía’s conviction stayed in the record and in the shock in patrons’ eyes when they walked into the house. There was no forgetting, because forgetting would be a betrayal of Clara.

But Tomás learned to sleep with his head on a pillow that did not press with cruelty. He learned to ask questions and feel his father answer. He learned to let a woman who had once knelt with a penlight take the space near his elbow at night.

The house had a different rhythm now. Marisol would sometimes stand at the service door and watch the boy throw a ball across the lawn. Once she would return to La Guerrero for long periods, and years later she would answer a letter from Alejandro asking if she could come home for a visit. She did.

There was no neat redemption for Lucía. There was no softening of what she did. Justice, when it came, was a tool that could not undo what had been done. But it also kept the ledger honest.

The last scene was a small one: a child asleep under a jacaranda, a woman who had dug with gloves folded into a chair, and a father who had learned to count cries as requests to be heard. There were scars—on papers, in memories, in a world that had been altered by greed and fear. There was also a tenderness that had been earned in the trenches of grief.

Tomás grew up with a story that had been told to him in parts, with an aunt who had been an inspector and an adopted mother who had been a nurse. He learned that names could be reclaimed and that love could be complicated and protective, and that sometimes the strongest thing a person could do was to keep digging until the truth surfaced.

He never cried in the same way again.